Welcome

From Chicago Department of Aviation Commissioner Jamie Rhee and Belmont Village Founder & CEO Patricia Will

We are so proud to have the opportunity to share this stunning collection of photos and stories of our senior veterans with the millions of travelers who pass through Chicago’s airports each year. We welcome guests to spend time with the remarkable veterans on our walls and in our communities, read their stories and walk away with a fresh perspective on our history and our future, from those who helped to create it. We are humbled daily by their service and sacrifices, and by those of the dedicated men and women who serve today.

With deepest gratitude and appreciation,

American Heroes Portraits of Service

Jeff DeBevec, curator

Read More CollapsePhotographs of Senior Veterans with Stories of Their Wartime Experiences by THOMAS SANDERS

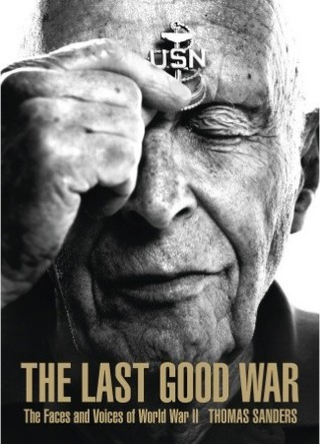

The power of portrait photography is immense and magical. A photographic portrait freezes an individual’s image in time, and when it’s done right, it can transcend time altogether to reveal multiple, deeper dimensions of person and place. Such are the photographs of Thomas Sanders, who in 2008 was commissioned by Belmont Village Senior Living to create portraits of seniors who had served in World War II. Sanders’ photographs are bold, honest, and insightful. Through the alchemy of lighting, posture and a nuanced use of artifacts, they capture both the vulnerability of age and the valor of youth in wartime. This is a remarkable creative achievement and a testament to Sanders’ talent as a portrait photographer.

The ranks of living World War II veterans are in inevitable decline. It is not unreasonable to think about this collection as part of a larger narrative, a photographic chronicle of a generation that began in wartime with compelling images by the battlefield and home-front photographers of the day – Edward Steichen, Robert Capa, Joe Rosenthal, Dorothea Lange, Alfred Eisenstaedt – and now finds its terminus with Sanders who is equally compelled to capture this story, now in its final chapter.

The Belmont Village American Heroes collaboration with Sanders continues as an ongoing effort to recognize and preserve the stories of its resident veterans. The photographs and stories are formally displayed at Belmont communities and have become an integral part of the company’s culture. The collection now includes veterans of the Korean and Vietnam wars, as well as those who have served in peacetime. Since its inception in 2008, the portfolio has grown to over 1,000 portraits of Belmont Village veterans, arguably the largest collection of its kind in the world. Sanders’ World War II portraits are featured in the award-winning book, The Last Good War, Faces and Voices of World War II, published in 2010 by Welcome Books.

The exhibitions presented at Midway International Airport and O’Hare International Airport are the first-ever public showings of the American Heroes collection, a unique collaboration with the Chicago Department of Aviation. The specially curated exhibits include a selection of images of veterans from cities across the U.S. and special sections dedicated to Chicago area veterans.

We are grateful for the sacrifices of all veterans and their families and are privileged to honor their bravery and selfless contributions in service to our country.

Heroes Gallery

The images selected for the Chicago Department of Aviation (CDA) galleries remain true to the project’s intent, showing a diverse group of men and women who served in a wide range of ranks across multiple branches of the United States Armed Forces.

- 1 of 64

Photographer's Statement

Read More CollapseThe first World War II veteran I photographed was Lt. Randall Harris. He showed me a six-inch scar on his stomach and told me his story. While stationed in Italy, his company’s mission was to take the eastern half of the Sicilian town of Gela and form a perimeter. At the beginning of battle, his company commander triggered an S-mine and was killed instantly. Steel balls from the mine flew in every direction and another S-mine exploded. Several of the balls hit Harris in his lower abdomen and legs. Randall took his canteen belt, tightened the strap around his wound and continued fighting.

He made it back to the aid station line at camp. As he waited, a medic came by and, seeing that Randall was critically injured, tried to move him to the front of the line. Lt. Harris would not budge, “No one touches me until all my men have been attended to.”

Randall shared his story with me in 2006, when I was a 21-year-old college senior, worrying about final exams, my future career, getting the phone number of the girl I was trying to date that weekend. When Randall was my age, his only goal was to live to the next day. Right then, I decided I was going to photograph and document as many WWII veterans as I possibly could.

I began traveling up and down the California Coast seeking out veterans and photographing a few men and women a day. Then I received a commission from Belmont Village Senior Living to photograph all of the veterans living in their communities. It was a dream come true.

I hope when people see my images of these veterans and read their stories, they become more appreciative of all who have served our country and fought our wars. It shouldn’t matter if a soldier saw battle or not, if they were prepared to fight or fought. They have all made sacrifices, and many have made the ultimate sacrifice. My great-uncle lost his life at the Battle of the Bulge. His family lost a brother, a son, an uncle. Like so many others, Bobby Sanders lost the chance to have a family, a career and a full life. Many of the veterans I’ve photographed have passed away. It is one of the most difficult parts of this project for me, but has also been a powerful reminder of why preserving their images and stories is so vitally important.

– Thomas Sanders https://tomsandersphoto.com

About

American Heroes: Portraits of Service began at Belmont Village in 2008 as a way to recognize the hundreds of veterans in residence in our communities. It is a dynamic, ongoing recognition project consisting exclusively of portraits by award-winning photographer Thomas Sanders.

The images selected for the Chicago Department of Aviation (CDA) galleries remain true to the project’s intent, showing a diverse group of men and women who served in a wide range of ranks across multiple branches of the United States Armed Forces. Their stories and attitudes vary with their experiences, but all share the common thread of service. The galleries are intended to honor these veterans and all who have served, before and since.

Uniquely designed by Belmont Village for the CDA, the airport galleries include dedicated sections of Chicago veterans, as a special gesture of gratitude and recognition from their hometown to these veterans and all Chicagoland service members.

Share your thoughts on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram with @Fly2Midway, @Fly2Ohare and @BelmontVillageSeniorLiving.

Project Partners

Belmont Village Senior Living and the Chicago Department of Aviation have proudly partnered to bring this unparalleled collection of veteran portraits and stories to the walls of Chicago’s international airports. The exhibit serves to preserve the histories of our most senior veterans and to highlight the contributions of all service members.

Special thanks to project co-sponsor, Chicago-based Harrison Street. A longstanding Belmont Village partner and a supporter of Armed Forces housing on U.S. Air Force bases, Harrison Street joins us in helping to recognize and pay tribute to the selfless service of these veterans.

“A brilliant collaboration of historic stories told from a variety of American soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who fought long and hard for the safety of their country.”